They didn't know we were seeds

Project/Artist Statement – Carol Wylie

In April of 2016 I attended the Saskatoon Holocaust Memorial service. As survivor Nate Leipciger spoke of his horrifying experiences in a Nazi death camp, and his ongoing efforts to educate and shed light on these atrocities, I was struck anew by the extent of abuse a human being can endure at the hand of another. Several events occurred following that service that brought to mind the issue of the residential school experience of 150,000 Indigenous children. Indian Affairs Superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott, in 1910, called residential schools “The Final Solution,” preceding Hitler’s similar pronouncement regarding the death camps and the “Jewish problem” decades later. Separating families, cutting hair, replacing names with numbers were oppressive methods of dehumanizing and othering. I learned that both groups of survivors have connected around strategies of survival and healing. Holocaust survivor Robert Waisman, who has met with Indigenous survivors and talked about his experience at Buchenwald, speaks of “a sacred duty and responsibility” toward helping residential school survivors heal. He stated, “we cannot, and we should not, compare sufferings. Each suffering is unique…I don’t compare my sufferings or the holocaust to what happened in residential schools. We did it [survived] – so can you.” Both Indigenous survivors and Jewish survivors speak of a solidarity forged from the shared need to find ways of healing personal and generational trauma in the wake of horrendous abuse and attempted genocide, and of the need to educate.

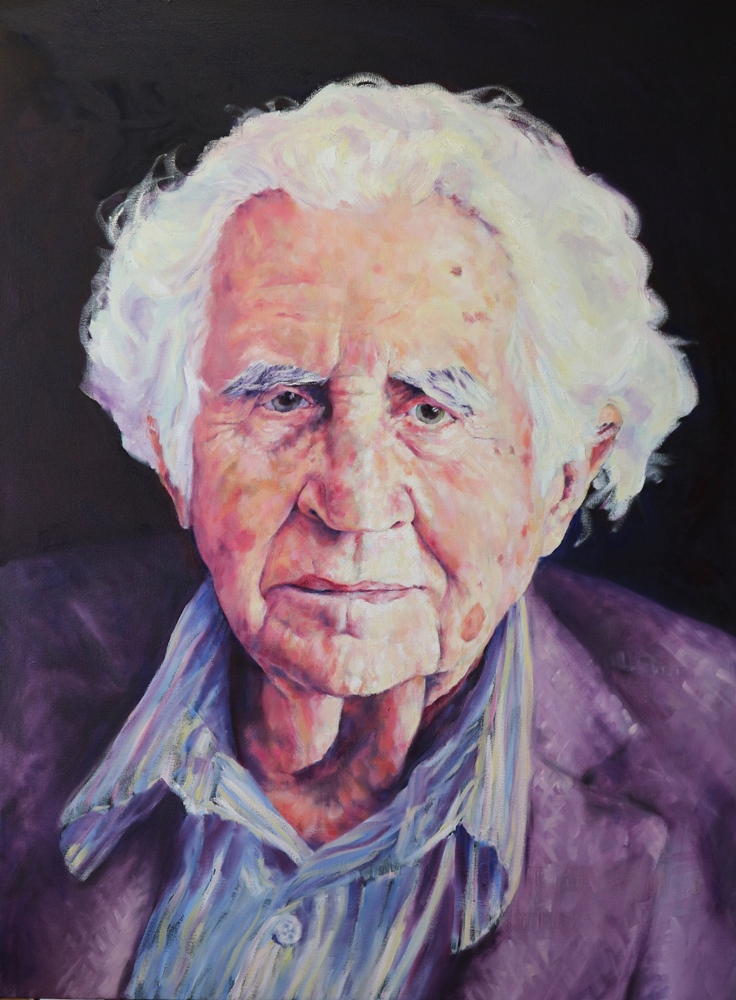

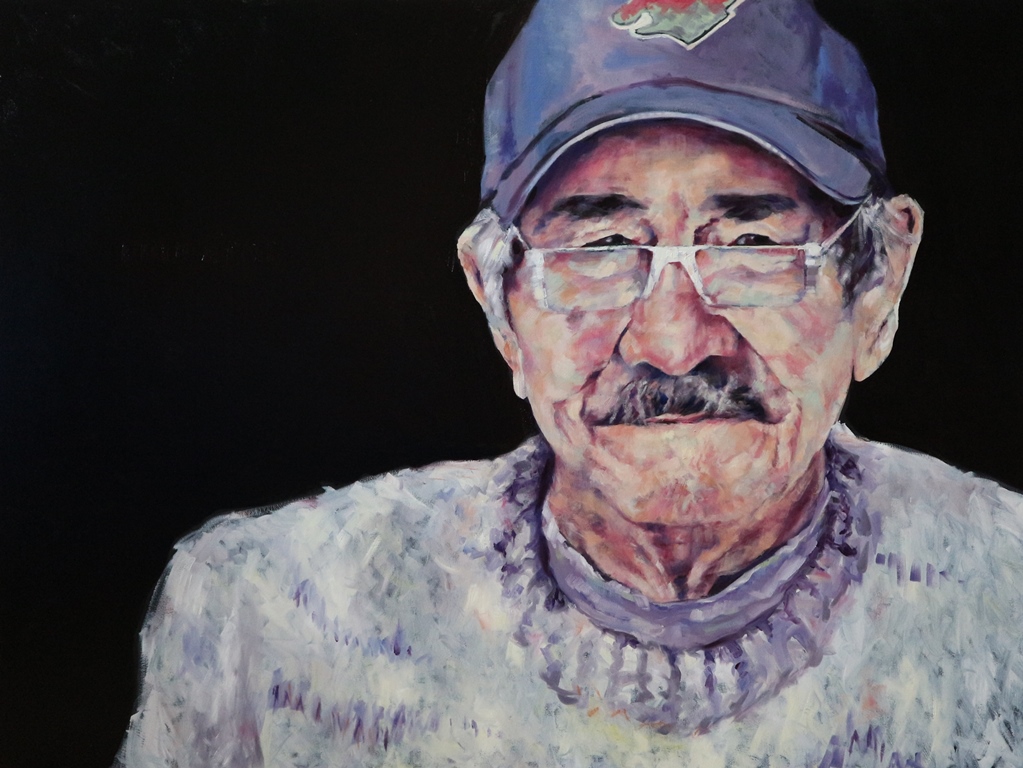

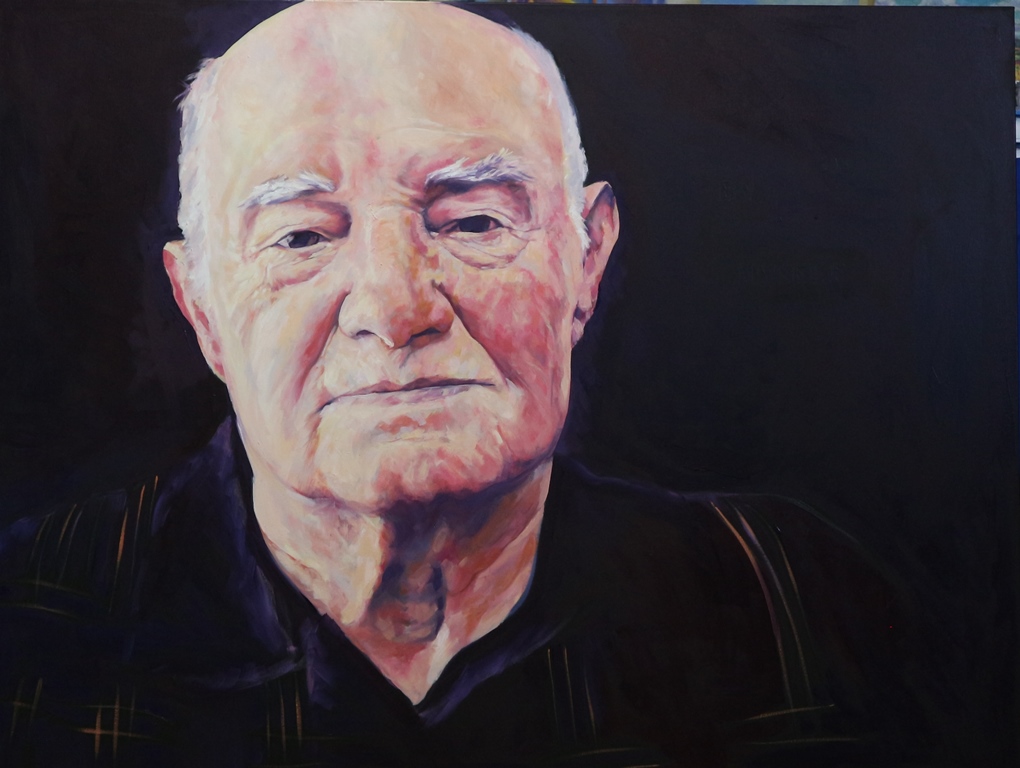

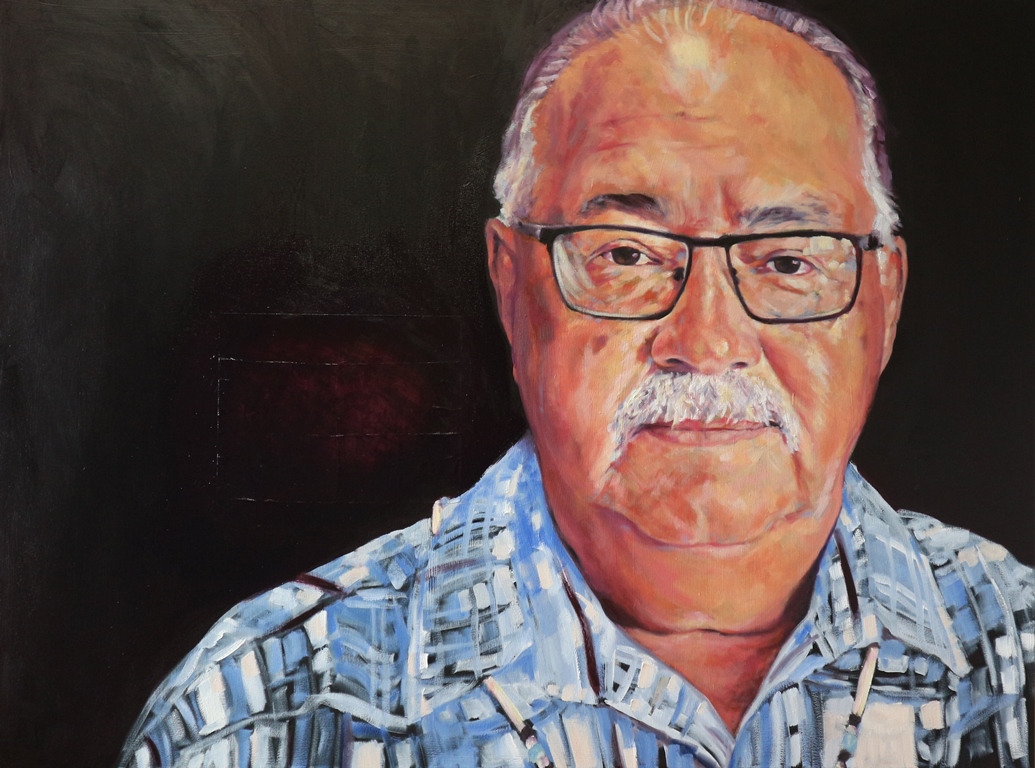

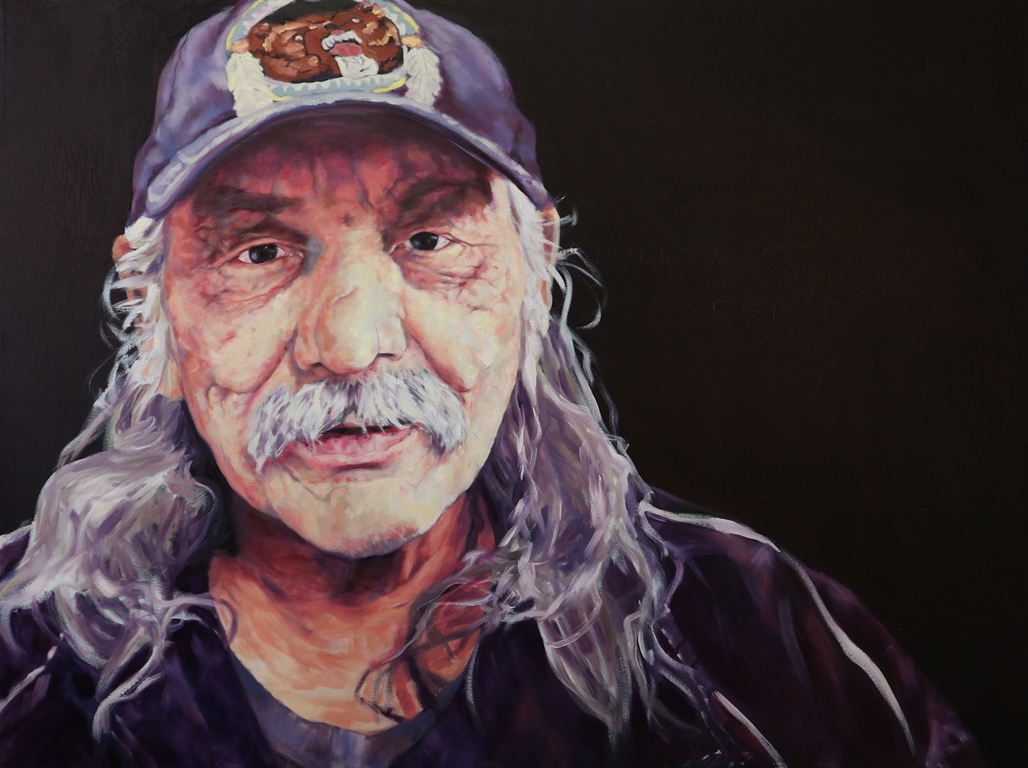

Holocaust survivors are elderly and dying, leaving fewer and fewer first-hand accounts. After hearing Nate speak, I felt the need to somehow acknowledge these extraordinary people who endured and survived, and to find a way to preserve that sense of the personal. The connection between holocaust and residential school survivors that emerged for me, as a settler in Saskatchewan with its notorious history of residential schools, was the impetus behind expanding the project to include portraits of residential school survivors. Perhaps hearing that history and those stories could be a small, personal step toward the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls for action, listening and bearing witness. All the residential school survivors who chose to participate entrusted me to share their history through portraiture with integrity. For this I am deeply grateful.

The painted portrait is the methodology through which I can offer the strongest statement. Maurice Merleau-Ponty speaks of the way the body is the site of perception and relationship to the world around us. It is how consciousness reaches out and allows us to simultaneously perceive and interact with the world. I engage the body as both subject and tool. The painted portrait is a meeting of two subjectivities requiring commitment, time, and an intimacy with another’s countenance. A portrait inhabited by the subject has the potential to offer a form of engagement with that person even in their absence. Through portraits of individual survivors, I hoped to create a silent dialogue between Jewish survivors and Indigenous survivors. Sketches, photographs, and interviews with survivors who generously collaborated with me on this project resulted in a series of eighteen portraits. The number eighteen in Hebrew tradition represents the word “chai” which means “life.” Those with whom I met spoke so honestly and poignantly that, in some cases, their words have been incorporated as text into the portraits. The project title is inspired by Greek poet Dinos Christianopoulos’ They buried us…they didn’t know we were seeds. My hope is that this work will give viewers a chance to encounter a survivor they may never meet. A single personal story can have more resonance than statistical abstractions, no matter how appalling. As numbers of holocaust survivors dwindle, and in anticipation of the same eventual loss of first-hand accounts from residential school survivors, these portraits will remain as echoes of individual strength and courage.

Empathy is understanding the pain and joy of others as equal to our own, leveling us within a shared human experience. This project explores memory, trauma, shared pain, the strength of the human spirit, and an enduring hope that in truly hearing one another’s stories and accepting deep in our bones that we are all part of the same human family, we will have less cruelty and more compassion.

*I would like to gratefully acknowledge the Saskatchewan Foundation of the Arts for their generous support of this project.

Click link for CBC National News Story on the project:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VyoEVuoM5Z4

Click link for Edmonton Community Foundation podcast about the Seeds project

https://www.thewellendowedpodcast.com/episodes/episode-133-parallels/

Click link for recorded conversation with Robby Waisman (Holocaust Survivor), Eugene Arcand (Residential School Survivor), moderated by Marcus Miller (Director/Curator Mann Art Gallery) and Carol Wylie (artist):

Click link for a video on the Seeds exhibition at the Estevan Art Gallery:

Click link for TBT Gallery Interview

Upcoming “Seeds” Exhibitions

TBT Gallery, Temple B’nai Tikvah, Calgary, AB, August 31 to December 1, 2024

St. Thomas More Gallery, University of Saskatchewan, June 7 to September 19, 2025